Eric Schwitzgebel alerted me to a post at the Leiter Reports blog on the work of Jonathan Strassfeld (University of Rochester), who has compiled a document with philosophers appointed at 11 doctoral programs in the United States between 1930 and 1979: Berkeley, Chicago, Columbia, Cornell, Harvard, Michigan, Princeton, Stanford, UCLA, U Penn, and Yale. I was curious whether appointments in this period could predict present day diversity for these programs. My prediction was that a higher percentage of women among those appointed in this period would predict a higher percentage of women among faculty and graduate students today. I also wondered, given my work with Eric Schwitzgebel, whether area of specialization would interact with this effect (in that work, women were shown to be more likely to specialize in Value Theory). Although this is not a formal analysis, it appears as though programs that appointed a higher percentage of women in this period do have a higher percentage of women and non-white graduates today, and that there is some interaction with area of specialization such that programs with more faculty in LEMM/analytic fields tend to correspond with lower percentages of women, and historical fields tend to correspond with higher percentages of women. Given this first pass look at Strassfeld’s data, I think it would be useful to attempt to collect this data for a larger set of programs, to more formally explore these connections. More details on my first pass look at Strassfeld's data below. (Numbers updated on 5/29/16 to reflect a change made to Strassfeld's data. Namely, I had incorrectly removed one woman faculty member from the analysis, which Strassfeld pointed out to me.)

recent posts

- (Very) Early Foucault on Humanism, Part 4: Kant, Anthropology, and Departing from Heidegger

- (Very) Early Foucault on Humanism, Part 3: Heidegger and Foucault on Kant

- AI Literacy Paper

- (Very) Early Foucault on Humanism, Part 2: Heidegger?

- (Very) Early Foucault on Humanism, Part 1: From Order back to Lille

about

-

If you’re an SSRN user, you got the notice in your Inbox yesterday; if you’re not, follow the links at the top of Leiter’s post here. Read the comments, too. It’s hard to know what to make of this acquisition, but for those not familiar, here’s a quick backgrounder: SSRN.com (“Social Science Research Network”) has, for a very long time, been a repository for freely available research online, particularly in law. Most law faculty post their papers on SSRN, where anybody else may freely download and read them. SSRN also has other categories: I post my papers there, and there’s an entire set of categories for philosophy. When you post a paper on SSRN, it makes you swear that you have the right to do so, and underscores that it does not take copyright in anything. I’m a heavy user of the site, as is every legal academic I know (that’s how I got to it: I read lots of law journal articles). Elsevier has now bought SSRN.

Philosophers tend to use academia.edu, which is unfortunate. You can’t download anything from the site without registering for it, and when you do, it tries to scrape the web and link your papers to your academia.edu site (or at least, it did when I make this mistake several years ago), and then sends you an email asking you to make sure the papers listed are all yours (the overinclusion in my case was comical, as there is somebody in physics whose initials are G Hull). You also get a barrage of emails: somebody just searched for you on google and found your academia.edu page! Click here to know where they were! Good grief. In computer terms, the site is basically trying hard to be sticky (causing people to go there and linger), and so it imitates Facebook, giving you lots of opportunities to curate your image, follow people, be followed, explore homepages, and so on, when all you thought you wanted to do was share your work for anybody who wanted to read it (the 5th comment on the Leiter page linked above goes into more detail). Did I mention that it comes with piles of corporate money?

-

The Supreme Court today issued a much-anticipated ruling in Zubik v. Burwell, the latest lawsuit against the Affordable Care Act's contraceptive provision. The ACA requires that insurance plans offer contraceptive coverage at zero cost, and includes a clause that employers who object to providing such coverage can request exemption from it, in which case the insurance company provides the contraception coverage, and the government pays them. In the current case, the nonprofit petitioners said that even being required to request exemption from the contraception mandate substantially burdened their religious freedom, since it would make them "complicit" in their employees' acquisition of contraception. As I do every time someone mentions this case, I'll point out now that these employees also receive wages from the company, which could also be used to purchase contraception. So that theory of the case would imply that wages are immoral. Given the political climate in the U.S., I should probably add that I consider this argument a reductio.

Now we know how the Hollow Claim ends. After oral argument the Court requested additional briefs to see, essentially, whether the parties could work things out themselves, providing both contraception and religious accommodati0n. Both parties submitted supplemental briefs indicating they could, and so today the SCOTUS ordered them to get busy on that project:

"Following oral argument, the Court requested supplemental briefing from the parties addressing “whether contraceptive coverage could be provided to petitioners’ employees, through petitioners’ insurance companies, without any such notice from petitioners.” Post, p. ___. Both petitioners and the Government now confirm that such an option is feasible. Petitioners have clarified that their religious exercise is not infringed where they “need to do nothing more than contract for a plan that does not include coverage for some or all forms of contraception,” even if their employees receive cost-free contraceptive coverage from the same insurance company. Supplemental Brief for Petitioners 4. The Government has confirmed that the challenged procedures “for employers with insured plans could be modified to operate in the manner posited in the Court’s order while still ensuring that the affected women receive contraceptive coverage seamlessly, together with the rest of their health coverage.” Supplemental Brief for Respondents 14–15.

In light of the positions asserted by the parties in their supplemental briefs, the Court vacates the judgments below and remands to the respective United States Courts of Appeals for the Third, Fifth, Tenth, and D. C. Circuits. Given the gravity of the dispute and the substantial clarification and refinement in the positions of the parties, the parties on remand should be afforded an opportunity to arrive at an approach going forward that accommodates petitioners’ religious exercise while at the same time ensuring that women covered by petitioners’ health plans “receive full and equal health coverage, including contraceptive coverage.” Id., at 1. We anticipate that the Courts of Appeals will allow the parties sufficient time to resolve any outstanding issues between them."

In the meantime, it is worth pointing out that this is an exercise in the Courts ordering biopolitics to happen, and rejecting efforts to get out of that process through judicial fiat. I mention that only because (shameless self-promotion), I think the logic, if not the language, is on the general same page as how the Courts handled school desegregation in its heyday: the Court sets the outer parameters, but basically they want a policy-making process to happen, if with juridical supervision.

-

by Eric Schwitzgebel

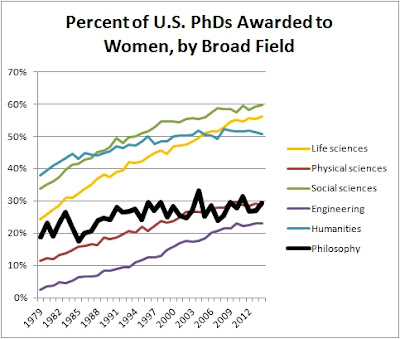

As Carolyn Dicey Jennings and I have documented, academic philosophy in the United States is highly gender skewed, with gender ratios more characteristic of engineering and the physical sciences than of the humanities and social sciences. However, unlike engineering and the physical sciences, philosophy appears to have stalled out in its progress toward gender parity.

Some of the best data on gender in U.S. academia are from the National Science Foundation’s Survey of Earned Doctorates (SED). In an earlier post, I analyzed the philosophy data since 1973, creating this graph:

The quadratic fit (green) is statistically much better than the linear fit (red; AICc .996 vs .004), meaning that it is highly unlikely that the apparent flattening is chance variation from a linear trend.

Since the 1990s, the gender ratio of U.S. PhDs in philosophy has hovered steadily around 25-30%.

The SED site contains data on gender by broad field, going back to 1979. It is interesting to juxtapose these data with the philosophy data. (The philosophy data are noisier, as you’d expect, due to smaller numbers relative to the SED’s broad fields.)

The overall trend is clear: Although philosophy’s percentages are currently similar to the percentages in engineering and physical sciences, the trend in philosophy has flattened out in the 21st century, while engineering and the physical sciences continue to make progress toward gender parity. All the broad areas show roughly linear upward trends, except for the humanities which appears to have flattened at approximately parity.

These data speak against two reactions that I have sometimes heard to Carolyn’s and my work on gender disparity in philosophy. One reaction is “well, that just shows that philosophy is sociologically more like engineering and the physical sciences than we might have previously thought”. Another is “although philosophy has recently stalled in its progress toward gender parity, that is true in lots of other disciplines as well”. Neither claim appears to be true.

[I am leaving for Hong Kong later today, so comment approval might be delayed, but please feel free to post your thoughts and I’ll approve them and respond when I can!]

-

When the North Carolina legislature passed – in 12 hours from start to governor's signature – HB2, consigning transgender individuals to the bathrooms of their "biological sex" as listed on their birth certificate, UNC''s new system president Margaret Spellings issued a prosaic statement that "university institutions must require" restroom access policies that comply with the law.

The US Dept. of Justice, following its letters to the governor, has now sent a letter to Spellings and other top UNC administrators informing them that HB2's bathroom provision violates both Title IX and the Violence Against Women Act. The system apparently nets somewhere around $1 billion in Title IX money annually. The letter does not (as popular media tends to report) threaten that money directly – but it does threaten to get a court order forcing the system not to enforce HB2.

-

In critical work on neoliberalism, there’s probably two or three main schools of thought. One approaches the subject as a matter of political economy. David Harvey, whose analysis is explicitly Marxian, is the most well-known figure in this approach; another prominent author in that camp is Philip Mirowksi. The other major school is broadly Foucauldian, taking its cue from Foucault’s Birth of Biopolitics lectures. A third group, represented by autonomist Marxists like Paolo Virno, Franco Berardi, and of course Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, attempt a synthesis (I won’t have much to say about them here). All sides have methodological critiques of the other; here I just want to note that the Foucauldians generally tend to be concerned with a topic that seems neglected in political economy: granted that neoliberalism expects us all to behave as homo economicus, defined as a risk-calculating, utility-maximizing investor in himself (gendered pronoun deliberate), how does neoliberalism get people to actually do this? After all, it is not a natural human set of behaviors. More specifically, not just how does neoliberalism get people to do this, but how does it get them to do so enthusiastically, treating the definition of the human as homo economicus as the true, correct and only way to be human? In other words, Foucauldians insist that critiques of neoliberalism need an account of subjectification.

Wendy Brown’s new(ish) Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution (Zone Books, 2015) makes a substantial contribution to the Foucauldian camp by focusing on “Foucault’s innovation in conceiving neoliberalism as a political rationality” (120). The political rationality is “governance” as “the decentering of the state and other centers of rule and tracks in its place the specifically modern dispersal of socially organizing powers throughout the order and of powers ‘conducting’ and not only constraining or overtly regulating the subject” (125).

-

by Eric Schwitzgebel

… and celebrating the death of children?

“Does it matter if the story of the escape from Egypt is historically true?” Rabbi Suzanne Singer asked us, her congregants, on Saturday, at the Passover Seder dinner at Temple Beth El in Riverside.

We’re a liberal Reform Judaism congregation. Everyone except me seemed to be shaking their heads, no, it doesn’t matter. I was nodding, however. Yes, it does matter.

Rabbi Singer walked over to me with the microphone, “Okay, Eric, why does it matter?”

I say “we” are a Reform Judaism congregation, but let me be clear: I am not Jewish. My wife Pauline is. My teenage son Davy is. Davy even teaches at the religious school. My nine-year-old daughter Kate, adopted from China at age one, recently described herself as “half Jewish”. We’re members. We volunteer, attend some of the services. Sometimes I try to chant the chants, sometimes I don’t. I always feel a little… ambiguous.

I hadn’t been expecting to speak. I came out with some version of the following thought. If the story of Passover is literally true, then there’s a miracle-working God. And it would matter if there were such a God. I don’t think I would like the moral character of that God, a God who kills so many innocent Egyptians. I’m glad it’s not literally true. It matters.

I find it interesting, I added, that we (“we”?) have this celebratory holiday about the death of children, contrary to the values of most of us now. It’s interesting how we struggle to deal with that change in values while keeping the traditions of the holiday.

-

In adding a clause to Hegel, Marx remarked once that the great world historical events occur twice: first as a tragedy, and then as a farce. For a 21st century version, I propose adding that it’s getting harder to tell the difference. I am of course talking about North Carolina’s infamous HB2, which requires trans* individuals to go to the restroom of their “biological sex” as recorded on their birth certificate, AND makes several forms of discrimination (racial, etc.) illegal in the state (but not against the LGBTQ) AND bars local municipalities from extending further protections (it does more, but those are enough for one blogpost). The clear intent, and the net effect, is to deprive gender non-conforming individuals from equal protection of the law, and to invite discrimination against them.

In defense of the inevitable firestorm this caused, most of the few state leaders who both support it and who have spoken on it have basically gone into a defensive crouch. The governor claimed to be “blind-sided” by questions about the law, and unclear about its implications. More generally, supporters busy themselves telling fairy tales about the danger to public safety that having “biological” men in the women’s room will cause, no matter how much those men have transitioned into being women. Nevermind that there is zero evidence that there has ever been a problem in this regard, including in the hundreds of jurisdictions that have passed ordinances like Charlotte’s, and nevermind that transitioning is about the most difficult possible way to prey on people in public restrooms. Oh, and nevermind that the law is without theoretical foundation unless you think that trans* individuals are sexual predators, and that cis folks are not.

On the farce side, this means that people who appear to be men will have to use the women’s room (and vice versa), which will almost certainly cause greater discomfort for more people than the previous status quo. On the tragic side, the law is totally unenforceable, and so encourages vigilantism against all gender non-conforming individuals, since they are now all on a continuum that ends with “not being not manly enough to use the men’s room.” As Mary Elizabeth Williams writes on Salon:

-

As noted in the APDA update posted over a week ago, we are in the middle of two important projects:

- We are adding individual editing to the website in May 2016. Up to March 2016, placement data were edited by project personnel, placement officers, or department chairs. In the future, individual graduates will have the option to claim their entry. To do this, we require a contact email for the graduates in our database. We currently have email addresses for roughly one quarter of the database. For graduates: to ensure that you are included among those who have access to individual editing, please provide your email address here: http://goo.gl/forms/mXUbpeH5ic

- Along with individual editing, in May 2016 we will add a brief qualitative survey for graduates. We will use linguistic analysis to compare these responses across graduates, connecting them to metadata on graduating institution, gender, graduation year, area of specialization, and placement type. Participants will be compensated for their time. Again, to do this, we require the contact email for the graduates in our database. For graduates: To ensure that you are sent the qualitative survey, please provide your email address here: http://goo.gl/forms/mXUbpeH5ic

Please feel free to send the form to past philosophy graduates you know who may want to be included! As it says above, time they spend filling out the qualitative survey in May will be compensated (by a $50 Amazon gift card raffle for every 50 participants). And note: it is our policy to treat the email addresses as private and accessible only by project personnel.

-

This is a brief notice that APDA has finalized its update for the 2015 report. Here is the report from 2015 and here is the update. Please contact me (cjennings3 at ucmerced.edu) with feedback or leave comments and suggestions below.

Update: I replaced one of the links as I noticed that the AOS table had been mismatched to the gender table.

Update (4/15/16): I will list here errors that are discovered in the data/report:

University of Washington–4 grads (2 2012, 2 2014) should be listed as temporary academic, but are currently permanent (but non TT) academic.

University of Texas, Austin–placement records are missing several graduates and should be checked against the placement page (the placement page was down when we attempted to check it in November).

University of Arkansas–this program was not contacted for data and should be included in future reports.